Distinguishing Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs) from Mutual Funds

Keith Fevurly, Investment Advisor, Integra Financial Inc. • June 3, 2020

Mutual funds and exchange traded funds are types of professionally managed assets, but there are major differences. First, a mutual fund (or its proper name, “open end investment company”), is priced only at the end of the trading day, when its “net asset value” (NAV) is determined. The NAV of any mutual fund is computed by taking the portfolio’s total market value at the end of any trading day, then subtracting any fund liabilities, and, finally, dividing the resulting number by the number of outstanding shares in the fund. The fund is said to be “open ended” since it continually offers new shares to investors and remains ready to buy back outstanding shares from investors. Alternatively, an exchange traded fund (“ETF”), trades like a stock, meaning an immediate price is obtained when there is a trade of the share (or more properly, the “depository receipt”). While the ETF is also valued according to its NAV at the end of the closing day, the more relevant value is its “intraday NAV”, the difference between its NAV and market price.

The key to properly diversifying a portfolio is to diversify “across and within” sectors of the market. There are 11 sectors of the market as follows:

A second major difference is the type of assets in which a mutual fund invests as compared with the ETF. There are numerous categories of mutual funds depending on the fund’s investment objective, but generally these categories are listed as part of a fund that invests solely in stocks or bonds or a combination of stocks and bonds, referred to as a “balanced fund”. A notable separate type of mutual fund is an “index fund” or a fund that invests only in the shares of a major index such as the Standard & Poor index of 500 stocks (“S&P 500”). Alternatively, an ETF typically invests solely in index funds. Indeed, an ETF is often described as an “index fund that trades like a stock”.

A final major difference is that most mutual funds (with the notable exception of the index fund) are managed “actively”. If the fund portfolio manager practices “active management” techniques, it means that the manager or investment company is attempting to outperform a broad market index, such as the S&P 500 Index of stocks, on a longer term or more-than-one-year performance basis. Alternatively, most ETF’s are managed “passively”. At the heart of “passive management theory” is a belief that any market or stock exchange is “reasonably efficient”, meaning that there is no immediately apparent way to outperform the broad market index. As a result, an ETF manager attempts only to match the market index and does not trade the portfolio’s holdings nearly as frequently as an “active manager”, thereby resulting in lower costs to the investor.

An investor’s annual total return, both in terms of dollars and percentage, from a professionally managed asset, such as a mutual fund or ETF, is heavily dependent on the fees charged to manage the portfolio. For example, if a fund imposes a management fee of one percent (1%) of its total NAV to manage the assets, an investor must achieve an annual return of at least one percentage more than the return the market index returns. Moreover, if the investment advisor charges a fee of an additional one percent to select the fund and manage the investor’s individual portfolio, the “bar” to overcome is now at least two percent (2%) more than the performance of the market index. Studies have shown that over a long period of time, for example 10 or 20 years, the recovery of these fees by the investor is extremely difficult to recoup. Thus, the greater the fees imposed by the fund or advisor, the more difficult it is to accumulate wealth over time.

A major advantage of the ETF form of professionally managed assets is its fee structure, resulting in a relatively low amount of fees imposed on the investor. In part, this is because a fee is only incurred if the underlying assets in the ETF are traded (bought or sold). Since the ETF is managed “passively”, and trading of its underlying assets is relatively infrequent, a fee advantage over the mutual fund results. Still another way in which ETFs achieve a fee advantage is because of how the ETF trades. Specifically, as mentioned previously, an ETF trades its shares like a stock. Accordingly, the sale of an ETF share from one investor to another has no impact on the value of the overall fund. Conversely, when a mutual fund shareholder sells his or her shares, they must be “redeemed” (bought back in cash) from the investor. Sometimes, this requires the mutual fund to sell shares to raise cash to cover the cost of the redemption. As a result, the operating expenses of the mutual fund are typically more as compared to the ETF.

For an individual interested in investing in a professionally managed asset, the question arises: “Which is best, the mutual fund or the ETF”? A related question is: In which category of mutual fund or ETF, such as stocks or bonds, should an individual invest? However, before answering these questions, an individual should understand that both mutual funds and ETFs provide a major advantage over individual stocks and bonds: that of, instant diversification. Diversification is the art of constructing a portfolio to exhibit less total risk without experiencing an equal reduction in expected return. The construction of a fully diversified portfolio is the major benefit that a portfolio manager and investment advisor “brings to the table” and how the advisor in part “earns his fee”!

The key to properly diversifying a portfolio is to diversify “across and within” sectors of the market. There are 11 sectors of the market as follows:

• Technology

• Financials

• Utilities

• Consumer Discretionary

• Consumer Staples

• Energy

• Healthcare

• Industrials

• Telecom

• Materials

• Real Estate

An individual can invest in a sector-specific mutual fund or ETF, but if doing so, has achieved only diversification “within” the sectors of the market. Rather, to achieve further diversification “across the market”, he or she should invest in several mutual funds or ETFs.

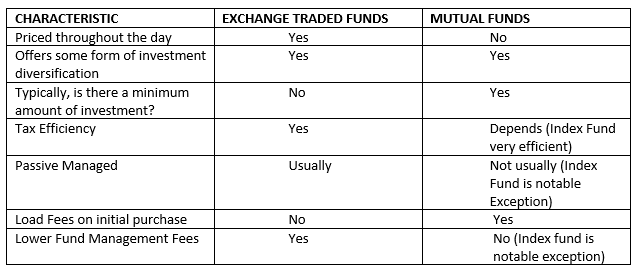

Here is a table summarizing the characteristics of ETFs as compared to mutual funds:

Here is a table summarizing the characteristics of ETFs as compared to mutual funds:

EXCHANGE TRADED FUNDS (ETFs) VERSUS MUTUAL FUNDS

I hope this letter finds you well and that you enjoyed a pleasant summer. As we wrap up the third quarter of 2025, the environment has been challenging, shaped by geopolitical uncertainty, persistent inflation, and a troubling jobs report alongside other unsettling headlines. Even so, markets largely looked past these concerns, focusing instead on strong corporate earnings growth—which ultimately drove new market highs. The Morningstar Broad Market Index was up 12.5 % for the year and 8.2 % for the quarter. From an economic standpoint, the data was mixed. We had real GDP growth at 1.3% versus .9% from the previous report. Wage growth was up, and the unemployment rate remained low at 4.1%. This contrasts with a slowing jobs report and inflation is still above the fed's stated goal of 2%. These conflicting reports created tension between the hope for more growth and the risk of a more significant economic slowdown. As usual, we navigated this environment by remaining disciplined. Our strategy continued to prioritize corporate earnings, being diversified, strong balance sheets and management. While some areas of the market underperformed, our allocations to the growth sector have again paid off handsomely with all the hope of AI. In times like these, it's easy to get caught up in the 24/7 news cycle and react emotionally to daily market fluctuations. We understand that seeing market volatility can be unsettling, but our job is to look past the noise and remain focused on the long-term fundamentals that drive wealth creation. Looking ahead, we believe the Fed will lower interest rates and that the market is stronger than many assume. As futurist Roy Amara noted, “We tend to overestimate the effect of technology in the short run and underestimate its effects in the long run.” Radio, air travel, and 3D printing come to mind as we contemplate the transformative potential of AI. In our view, the companies we invest in are well-positioned not only to weather economic headwinds but also to thrive when conditions improve. Stay tuned we are living in interesting times. In closing, know that our commitment to your financial well-being is unwavering. If you have any questions or if your circumstances have changed, we encourage you to reach out to schedule a conversation. We look forward to speaking with you soon and to a productive end of the year. Thanks for the trust you place with us. Yours Truly, Willis Ashby, President CFP®

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) was signed into law by President Trump on July 4, 2025. Among its many provisions is an addition to the numerous tax vehicles available to save for a child’s college education: the so called “Baby Savings Account” or better known as the “Trump Savings Account”. It is created as a special savings account for children under the age of 18 and operates the same as a Traditional IRA after January 1st of the year when the child turns age 18. Here is what you need to know about this new account: 1) What is the effective date of the Trump Savings Account (the account)? July 4, 2025 or when the OBBBA was signed into law. However, under the law, no Trump Savings Account contributions can be accepted until 12 months after enactment of the OBBBA or July 4, 2026. 2) Who owns the Account? Similar to a Section 529 Plan or Education Savings Account (ESA), the account is owned by the child or beneficiary of the account. Before establishing the account, the child must have a Social Security number, already a requirement of the Federal tax law. The IRS is expected to announce further rules about the establishment of and tax reporting for the account. 3) Who and how much can be contributed to the account? There are any number of potential individuals or entities that can contribute to the account, including parents, guardians, grandparents, employers, and for children born between specific dates in the OBBBA legislation, the Federal government. Parents and other individuals may make contributions of up to $5,000 annually. Employers may contribute up to $2,500 annually for an employee or employee’s dependent who is under the age of 18. The Federal government may deposit a one-time $1,000 contribution for children born between January 1, 2025 and December 31, 2028. Finally, the employer contribution counts against (reduces) the $5,000 overall limit, but the one-time Federal government contribution does not count against the limit. 4) In what investments may the account contributions be made? Currently, the contributed monies may only be invested in an index mutual fund or exchange-traded fund (ETF) with an annual management fee of no more than 0.1% of the account balance. It is anticipated that future regulations will permit contributions in other investment vehicles, similar to Section 529 private savings plans. 5) When must contributions to the account be made (the contribution deadlines)? Account contributions must be made by December 31st of the contribution year. In the year the child turns age 18, the Traditional IRA contribution rules apply, meaning the contributions may be delayed until the tax filing date (with extension) for that contribution year. As an example, if the child turns age 18 on September 15, 2043, the account contribution need not be made until April 15, 2044 or October 15, 2044 with extension. 6) How is the account taxed until the child attains age 18? The funds in the account grow tax-deferred until the child attains age 18. Contributions from individuals are made with after-tax dollars, similar to a 529 plan. Employers may treat the contribution as taxable wages to the employee or employee dependent; therefore, the contribution is deductible as a business expense and made from pre-tax dollars. The one-time governmental contribution to the account is a tax free contribution. 7) What happens to the account when the child attains age 18? In the year the child turns age 18, the Traditional IRA rules apply. This means the account becomes subject to normal IRA rollover rules (once a year in most cases) and future required minimum distribution (RMD) rules. As a result, if distributions from the account are not made at age 18 (presumably, for college expenses), then the account may be used as a Traditional IRA retirement plan for the child/adult. However, be aware that Traditional IRA retirement plan penalties apply, such as the 10% premature distribution penalty if funds are taken before the owner turns age 59.5 (unless an exception applies). 8) When can distributions from the account be made? In the year the child/owner turns age 18, unless an exception applies (such as the death of the child). Since the contributions by an individual to the account are made with after-tax dollars, and therefore create taxable “basis”, the distributions are not taxable. In contrast, any employer contributions and the one-time Federal government contribution are made with before-tax dollars (a deduction applies), no basis is created and the distribution of this part of the account is fully taxable. Earnings are also fully taxable when distributed. In summary, for college education savings purposes, a Section 529 plan is still likely preferable since such plan provides for tax free distributions if used in payment of college expenses. However, the Trump Savings Account may be a desirable choice if wanting to establish a combination college education/Traditional IRA retirement plan for a child at an early age. The account is also the only savings vehicle featuring a Federal government contribution, although only temporarily. Talk to your advisor to determine which accounts best fit your situation. Please feel free to contact your Investment Team at Integra Financial, Inc. if there are any questions about this new investment savings account.

On July 4, 2025, President Trump signed the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) into law. Likely, the most important provision of OBBBA was the “permanent” extension of the lower income tax brackets from the 2017 Tax Cut and Job Act with no expiration date. However, be aware that the term “permanent” in the political world of Washington, DC, simply means that the current tax brackets only exist until a later Congress changes them and obtains the approval of the President then-in-office. Here are the current (2025) “permanent” income tax rates for married filing jointly (and single) taxpayers: • 10% on income up to $23,850 (single: $11,925) • 12% on income from $23,851 to $96,950 (single: $11,926-$48,475) • 22% on income from $96,951 to $206,700 (single: $48,476-$103,350) • 24% on income from $206,701 to $394,600 (single: $103,351-$197,300) • 32% on income from $394,601 to $501,050 (single: $197,301-$250,525) • 35% on income from $501,051 to $751,600 (single: $250,526-$626,350) • 37% on income over $751,600 (single: over $626,350) Moreover, the tax brackets continue to be adjusted for inflation each calendar year. In addition, the higher standard deductions from the 2017 Act were made “permanent” and increased further for the year 2025: • For single taxpayers: $15,750 • For married filing jointly: $31,500 • For seniors (individuals age 65 and over), a new senior citizen deduction of $6,000 for those seniors with Social Security income was enacted ($12,000 for married filing jointly taxpayers). However, the full deduction is available only for single filers with an adjusted gross income (AGI) of $75,000 or less, or married filing jointly couples with an AGI of $150,000 or less. The deduction is completely phased out for single filers with an AGI above $175,000 and married filing jointly taxpayers with an AGI above $250,000. Finally, the provision applies only for taxable years 2025-2028. Other notable “permanent” tax provisions implemented by OBBBA are: • The estate and gift tax exemption equivalent amount is increased to $15 million per person (effective in 2026) and is indexed for inflation annually (Note: the 2025 exemption was $13,990,000 per person.) • The 20% small business (Qualified Business Income or QBI) deduction first enacted in the 2017 Act. • 100% bonus depreciation deduction for qualified tangible property acquired by a business after January 20, 2025 is reinstated. • The child tax credit is increased from $2,000 to $2,200 for each qualifying child under the age of 17. The credit phases out for single taxpayers with AGI of $200,000 and $400,000 for married filing jointly taxpayers. • The existing limit allowing an itemized deduction of up to 60% of AGI for cash gifts to qualified charities is extended with no expiration date. However, beginning in 2026, the percentage charitable deduction for itemizers is restricted to no more than 0.5% of the taxpayer’s AGI. • Starting in 2026, a new charitable deduction for non-itemizers is introduced into the law. These taxpayers can now claim a deduction for charitable contributions of cash capped at $1,000 for single taxpayers and $2,000 for married filing jointly taxpayers. A series of temporary tax provisions effective only for tax years 2025-2028, unless otherwise noted, are also implemented by the OBBBA legislation. Here is a summary: • The State and Local Tax (SALT) itemized deduction is increased from $10,000 to $40,000 from 2025-2029. The deduction increases 1% per year from 2026-2029 and is phased out with income starting at $250,000 for single taxpayers and $500,000 for married filing jointly. The deduction is phased out completely at $300,000 single filing status and $600,000 married filing jointly. • Effective for auto loans starting after 12/21/2024, interest is deductible for cars, vans, and trucks weighing less than 14,000 pounds whose final assembly occurred in the United States. • A deduction for overtime pay capped at $12,500 for single filers and $25,000 for married filing jointly. The deduction is phased out for individuals with AGI exceeding $150,000 for single filers and $300,000 for joint filers. The deduction applies to federal income tax, reducing the overtime wages included in the individual’s taxable income. Finally, there are several new tax provisions included in the OBBBA legislation. Among these, are: • No federal income tax on tip income capped at $25,000 per year. However, the tip income is a non-itemized deduction and not an exclusion from taxable income. The deduction is subject to income limitations: for single filers, it begins to phase out at $150,000 of AGI and $300,000 for married filing jointly taxpayers. For self-employed individuals, the deduction is limited to the business’ net income (excluding the deduction itself). • For children born between 2025-2028, parents can open special “Baby Savings Accounts” or “Trump Accounts”. These accounts are similar to traditional IRAs (but with special rules) for dependent children under the age of 18 where parents or guardians can contribute up to $5,000 annually, and employers can contribute up to $2,500 annually. Contributions are made with after-tax dollars, but investment growth is tax deferred. Moreover, from 2025-2028, a one-time $1,000 federal government contribution may be made for eligible children. Distributions from such accounts are prohibited until January 1st of the year the child/beneficiary attains age 18, at which point the account is treated like a traditional IRA. • No federal income tax on overtime pay as discussed above under the section on temporary tax provisions. This provision is particularly important for service workers, such as restaurant wait staff and delivery drivers. If you have any questions about any of these provisions, please contact the Investment team at Integra Financial, Inc. While we are prohibited from giving specific tax advice, we can discuss how tax law and tax changes impact your future personal financial planning.

I hope you had a joyful and meaningful Fourth of July. I hope you spent it surrounded by family and friends. Governments have come a long way since the Magna Carta in 1215, followed by the English Bill of Rights in 1689, and eventually our own U.S. Constitution. Despite our many flaws—and we certainly have them—I’m grateful to be an American. As is tradition, we read the Declaration of Independence on the 4th. It’s a powerful reminder of how this nation came into being and the principles it was founded upon. What a Quarter After “Liberation Day” was announced on April 4th, concerns about inflation and a potential global trade war sent markets tumbling down -11% within days. Add to that the uncertainty surrounding new tariffs and the now passed tax bill, and it’s easy to understand the market’s volatility. Yet, the Morningstar Broad Index ended the quarter up 11.14%, and is up 15.30% for the year. How is that possible? Inflation, once feared to spiral, is now hovering near the 2% target. The anticipated global trade war has not materialized; instead, we may be witnessing a resetting of global trade relationships. Oil prices have declined after a brief spike due to tensions in Iran and the Strait of Hormuz. The trade deficit has narrowed, and a weaker dollar is helping boost U.S. exports. A Growing Concern: The National Debt While markets have shown resilience, we must also acknowledge a growing structural challenge: the federal debt, which now exceeds $36.2 trillion. With approximately 153.8 million taxpayers, that equates to over $235,000 per taxpayer. This level of debt raises serious questions about long-term fiscal sustainability. Despite the top 10% of earners paying 72% of all federal income taxes, the gap between revenue and spending continues to widen. The top 1% alone—those earning over $663,000—contribute 40.4% of all income taxes. Meanwhile, the bottom 50% contribute just 3%. Even if we were to tax the entire net worth of all U.S. billionaires—estimated at $5.5 trillion—it would barely make a dent in the total debt. This underscores the size and complexity of the issue and the importance of thoughtful, long-term policy solutions. It appears we cannot tax our way out and if we are not willing to cut spending it looks like the only reasonable option is to grow our economy as a way out. As always, Keith, Nick, Alison, and I are here to help you navigate these uncertain times with clarity and confidence. Please don’t hesitate to reach out with any questions or concerns. Yours Truly, Willis Ashby, President CFP® Govinfo.gov - Usadebtnow.org - Fiscaldata.treasury.gov - Taxfoundation.org - Bloomberg's billionaire index - Forbes - First Trust - WSJ - Morningstar

I hope this letter finds you well. As I sit down to write this, recent events—particularly the tariff announcements—have prompted me to revisit my initial draft. It’s safe to say that the current climate is far from ordinary. The Morningstar Broad Market Index posted a decline of 4.94% for the quarter. As I mentioned in my previous letter, I anticipated some jolts perhaps I should have emphasized the word “JOLTS” a little more! The much-discussed “Trump Rally” from last quarter has vanished. While the short-term picture may be concerning, it’s important to remember that the S&P 500 posted impressive gains of over 20% in both 2023 and 2024. As a result, we’ve seen a market that was overheated due to hype surrounding AI and other speculative factors, which inflated valuations. To put this into perspective, the Price-to-Earnings (PE) ratio for the Growth Index stood at 41.9, while the Value Index was at 18.4. Historically, the market PE ratio has hovered around 16, we are still working our way back toward more reasonable levels. The stated goals to bring key industries such as steel, automobiles, pharmaceuticals, lumber, and semiconductors back to the U.S. stems from a concerning trend: industrial production in the U.S. has increased by only 4.3% over the past 25 years—an annual growth rate of just 0.2%. Additionally, there’s a broader conversation around our national spending habits: while we collect $4.9 trillion in all taxes, we’re currently spending $6.75 trillion. These economic actions are intended to address these fundamental issues, with efforts aimed at reviving domestic manufacturing and resolving our spending imbalance. While these changes have immediate effects, the hope is that we avoid prolonged negative consequences. Some economists believe that the short-term pain will lead to long-term gain, while others question the wisdom of these actions. Remember Paul Volcker’s actions in the Reagan era of sky-high interest rates crushing the economy but ultimately set the stage for stronger, more sustainable growth. As history has often shown, economic cycles tend to repeat themselves, and I am hopeful that history can repeat itself and we’ll see positive results in the long run. I don’t think anyone can predict the long-term impact. We are comfortable with what we have paid for our positions and while the market may currently disagree with us, our long-term focus has historically paid off. The experiences of 2008 and 2009 serve as a recent reminder that sticking to a disciplined focus can ultimately yield positive results. As Warren Buffett famously said, “Stocks climb a wall of worry.” When fear drives others to the exits, it often creates opportunities for those who stay focused on the bigger picture. On a different note, we’ve recently encountered some technical issues with our email system. If you’ve reached out to us and haven’t received a response within a couple of days, please feel free to call us directly. Some emails are unexpectedly ending up in our enhanced security filters, and we are working diligently to resolve the issue. Lastly, I want to remind you to stay vigilant against online scams. These fraudulent schemes are becoming increasingly sophisticated, and even the most cautious individuals can fall victim. It’s more important than ever to be cautious when navigating the digital landscape. We truly appreciate the trust you place in us, and we’re always here to answer any questions or address any concerns you may have. Yours Truly Willis Ashby, CFP President Morningstar, WSJ, First Trust, MSNBC, BMO, ZACKS

Happy New Year! We hope you had a wonderful holiday season and wish you prosperity, good friends, and good health for 2025 and beyond. We are pleased to report that the broad Morningstar index increased by 24.09% for the year and 2.57% in the fourth quarter. The "growth" segment of the market, particularly companies like Apple, Microsoft, NVIDIA, Amazon, Alphabet, Meta, and Tesla, has been a major contributor to this performance. Together, these seven companies are valued at approximately $17.92 trillion, which represents around 44.80% of the S&P 500. Their performance remains a significant driver of broader market trends. Several key events have recently influenced the financial landscape: The post-election “Trump Rally.” Bitcoin's significant rise, recently reaching around $100,000. Potential tariffs and their uncertain effects. Government debt interest payments surpassing defense spending, ~$1 trillion vs ~800 billion respectively. A notable increase in government employment in 2023, with 709,000 jobs added, a jump from 299,000 in 2022 and 392,000 in 2021 (source: www.bls.gov). The establishment of the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE). The full impact of these events is still unfolding, but potential risks to market stability include tariffs, government debt, and the new DOGE department. While tariffs could have far-reaching effects, it is important to recognize that the policies discussed during campaigns may not align with actual implementation. Government debt may not pose an immediate concern, but over time, the bond market may react to the growing debt load, leading to necessary spending cuts. Though such measures could be painful in the short term, they may be necessary for long-term economic stability. The potential impact of the Department of Government Efficiency remains unclear. Elon Musk’s restructuring of Twitter (now X), which resulted in the elimination of thousands of jobs, has been seen as an effort to increase efficiency. Historically, the closure of government departments has been rare; the only significant example occurred during the Carter administration, when Alfred Kahn successfully dismantled the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB), leading to lower airline prices and more travel options. Overall, we expect the companies we monitor and invest in to remain profitable. Despite potential disruptions, 2025 is likely to be another positive year for the market, though some volatility or "jolts" along the way should be anticipated. Enclosed is our annual privacy notice (mailed letters). Additionally, if you would like a copy of our ADV, it is available on our website or can be sent upon request. Lastly, I want to express my gratitude to Kathy, Nick, Keith, and Alison for their excellent work. Please feel free to contact us with any questions or concerns. We remain committed to providing the best financial advice to support your well-being. Sincerely, Willis Ashby, President Integra Financial, Inc. 5105 DTC Parkway, Suite 316 Greenwood Village, CO 80111 303-220-5525 / 303-689-0973 FAX Bureau of Labor Statics, Wall Street Journal, 1 st Trust, Morningstar, Zacks Research, Co-pilot &/or ChatGPT

I hope you had a wonderful summer and are enjoying weather similar to what we have in Colorado. The Morningstar broad index rose by 3.59% this quarter and is up 19.65% for the year. In a long-anticipated shift, value stocks—such as Costco, Comcast, and Home Depot—have outperformed growth stocks like Google and Amazon. The growth sector, which has led the market for so long, is now seeing stretched valuations and limits to growth, making the value side increasingly appealing for investment. As we focus more on value investing, it’s rewarding to maintain a diversified portfolio that includes both value and growth stocks. Reflecting on the past year and beyond, I’ve been reminded that “the market climbs a wall of worry.” It can be challenging to invest when headline news seems discouraging, but I’ve witnessed this pattern often enough to firmly believe that the best strategy is to enter the market and stay invested. Many of you who have been with us for a decade or more can attest to the benefits of this approach. Viewing investments through a long-term lens—thinking in decades rather than years—helps manage the inevitable market fluctuations. I don’t want to come across as overly optimistic, but there are positive signs: inflation is declining, incomes are rising, and personal savings rates are up. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is also on the rise, with many corporations exceeding their earnings expectations. Historically, during periods of high inflation, like the Carter years, the stock market has proven to be an effective hedge against rising costs. As expenses—wages, goods, and taxes—increase, the value of stocks tends to follow suit, as corporations pass these costs onto consumers while striving to maintain their profit margins. Nick, Keith, Alison, and I are closely monitoring various factors that could impact the market and your portfolios. As always, we’re keeping an eye on the overall economy, particularly monthly employment numbers. Currently, over 60% of new jobs are in government or government-related sectors, which is less favorable than if the majority were in the private sector. The Federal Reserve has recently lowered the Fed Funds Rate by half a percent, a move prompted by falling inflation that appears to be trending toward the target rate of 2%. This reduction has been celebrated on Wall Street, as it lowers the cost of borrowing, benefiting both businesses and the government. Another trend we’re addressing is the stock-to-bond ratio in your portfolios. The stock side has grown much faster than bonds, for example, an initial 50/50 allocation is now closer to 60% stocks and 40% bonds. To rebalance your portfolio, we will sell some stocks and buy bonds to return to the desired ratio that best suits your investment strategy. In closing, I want to emphasize the importance of being vigilant with your online activities. The number of malicious actors attempting to hack personal information is increasing daily, so please take precautions. If you have any questions or if your financial situation changes, don’t hesitate to reach out. Alison, Keith, Nick, Kathy, and I appreciate your trust and are here to support you. Willis Willis Ashby, President Integra Financial, Inc. 5105 DTC Parkway, Suite 316 Greenwood Village, CO 80111 303-220-5525 / 303-689-0973 FAX

Salary-reduction-type retirement plans have, for some time, permitted so-called “hardship distributions” or “hardship withdrawals” prior to a participant’s retirement date. Salary-reduction-type plans include Section 401(k) plans available to for-profit employees, 403(b) plans for not-for-profit employees, and 457(b) plans for State and local government employees. Generally, such distributions are includible in a participant’s income and are subject to an “early distribution 10 percent penalty”, unless an exception applies.

Some points to consider: 1) Likely the biggest distribution question that a 401(k) participant asks is: should I rollover the proceeds to an IRA or retain it within the 401(k), assuming the plan sponsor allows that? There is no certain answer to this question, although in the majority of situations, it is preferable to roll the proceeds because of participant control of the account. See Willis, Nick, or Keith to begin the paperwork for a Rollover IRA.